The Jago Museum is undoubtedly one of the most innovative and interesting art sites in Naples in recent years. It is a space dedicated to the iconic works of Jacopo Cardillo, a sculptor known by his stage name Jago, who has quickly become a reference point for contemporary Italian and world art.

The location of Jago's museum is a symbolic one: we are in the Church of Sant'Aspreno dei Crociferi, in the heart of the Rione Sanità. It is a spot that has quickly become a place of worship for art lovers. The Museum of Jago is among the attractions of the Naples Pass, so you just have to take advantage of it and visit it now!

The Jago Museum in Rione Sanità: beauty can save

Jago's museum opened in Naples in the Church of Sant'Aspreno ai Crociferi in May 2023, although the link between Jacopo Cardillo, born Jago, and the city has roots born a few years earlier. It all stems from the work of Don Antonio Loffredo, rector of the church as well as founder of La Paranza Cooperative, who has always been close to charitable and cultural initiatives for the Rione Sanità.

Among the projects pushed by La Paranza is the Luce project, behind which is the reopening of the Church of Sant'Aspreno ai Crociferi with the consequent opening of the museum. It is the heart and work of rebirth of the Loffredo neighborhood that prompted Jago to open his exhibition here, to bring his works here.

The artist admitted that this redevelopment action “restores dignity and function to the abandoned, giving it back its essence.” This human design is fully reflected in Jago's artistic poetics, with the latter always giving center stage to the weakest, the marginalized and those who have no voice. A social and human art, which finds its best possible expression in this context.

Jago museum and the true realism of its work of art

The Jago museum present in Naples' Rione Sanità is special because it presents to the public all the major works of the Lazio-born artist. Going in order, however, we start with the early works, particularly “Self”: this is a half-bust of his, whose main feature is the hollowed-out eyes, staring at the audience; this is because it is the action of admiring the work that makes art progress, it is the audience that makes art such.

Stealing the eye then is “Hand,” depicting the hand of Jago's grandmother, who despite being afflicted with Parkinson's disease always had her red nail polish on her fingers. She, a bond so dear to the artist, who had been the only person to believe in his artistic dream from day zero.

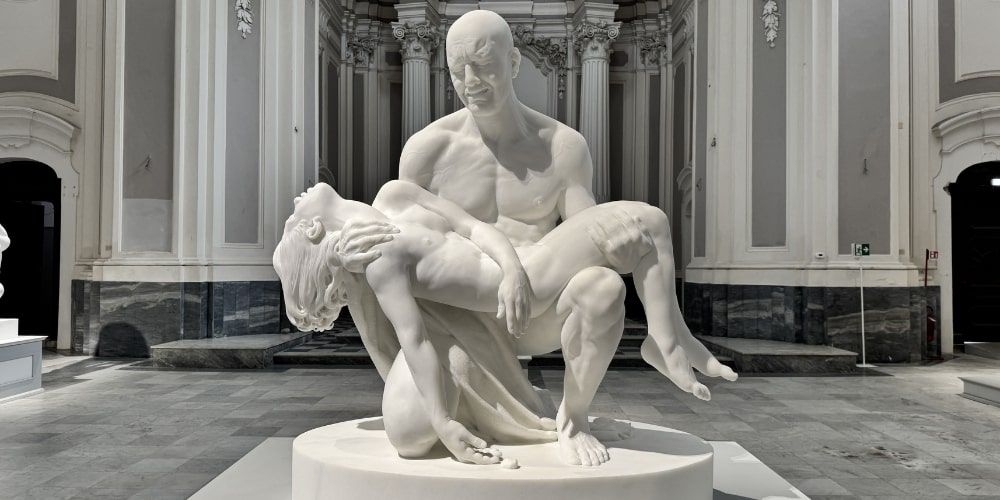

We then find among others the “Mineral Heart,” which is an anatomical heart, but that was not enough for the artist. So here is the birth of “Circulatory Apparatus”: 30 hearts and a system that closes in a circle, a symbol of eternity and perfection. Always stealing the eye, however, is “The Pieta,” perhaps Jago's signature work: the distinctiveness lies not only in the vivid and clear suffering, but in the asexuality of the dead body that focuses on the person, not the gender.

Let us also not forget “The David,” which is still in the works (now measuring about 1.60m, it will come to be about 4m), and “Venus,” depicted with an old woman, rough and hairless, to affirm that Venus is such always, even in old age. For it is from imperfections that true beauty, authentic beauty, is derived.

Greek mythology in Jago's art

There is also room for classical mythology in the Jago Museum, where two very interesting works with a great story behind them stand out to the eye. The first is that of “Narcissus,” which traces the myth according to which a young hunter, named Narcissus precisely, falls in love with his reflection in the water as a divine punishment. His end is a tragic one, for he ends up dying in the lake in which he was mirrored.

Jago goes beyond myth in his play because he contrasts Narcissus with the body of a woman, who represents the inner self, invisible from the outside. The hunter's hand, however, was not sculpted, because it is believed that he was able to dig into his self and go beyond himself, beyond the myth.

The other major work of a classical nature is “Ajax and Cassandra,” placed right in the center of the nave of the church. We are in the context of the Trojan War; the priestess Cassandra is found by Ajax, prince of Locris, and is raped by him. Again, Jago attempts to twist mythology by reaffirming goodness and positive feelings.

In fact, the artist freezes the second in which she freezes him, as if therefore to curb the violence. The intent is to give Cassandra a different epilogue, a message of hope that can be safely expanded to any context of violence and abuse. The human artistry of Jago is thus reaffirmed, finding here perhaps one of its highest expressions.

Visit the Jago Museum with Naples Pass

The Jago Museum has quickly become a mainstay of contemporary art in Naples, a must-see agglomeration of art and beauty. In its favor, moreover, is the extreme ease with which one can reach the Church of Sant'Aspreno ai Crociferi; just take the subway to the Piazza Cavour stop on Line 2, or the Museo stop on Line 1. It is open every day, on weekends even in the afternoon (10 a.m. to 2 p.m. and 3 p.m. to 7 p.m.),

We emphasize how the Jago Museum is among the many attractions included in the Naples Pass, an essential tool for visiting Naples, complicit with all the benefits and discounts present. You just have to hurry up and visit the exhibition, thus catapulting you into the artistic universe of Jago, a true national artistic pride in Italy and the world!

Lascia un commento